“Unable to Obtain Documentary Confirmation” – Due Diligence and Questions Posed by the Collecting History of The Cleveland Museum of Art’s Drusus Minor Head

|

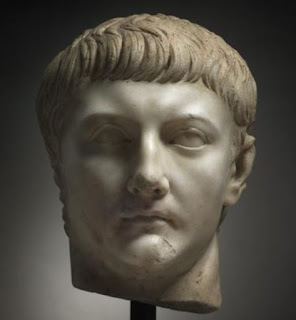

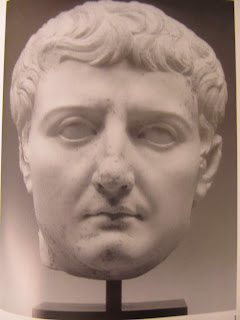

| The Portrait Head of Drusus Minor acquired by the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Magdalene Tiberius share many similarities. |

[UPDATE: In a press release by the Cleveland Museum of Art dated April 18, 2017, the museum announced that it would repatriate the marble head of Drusus to Italy. The CHL blog post below, dated August 12, 2015, appears to have played some part in the cultural artifact’s return.]

The Cleveland Museum of Art announced this week that it was accessioning a marble head depicting Drusus Minor, the son of Roman Emperor Tiberius. That acquisition appears on the Association of Art Museum Directors’ (AAMD) object registry because the Cleveland Museum seeks an exception to AAMD’s “1970 rule.”

The Report of the AAMD Task Force on the Acquisition of Archaeological Materials and Ancient Art (Revised 2008) declares, “Member museums normally should not acquire a work unless provenance research substantiates that the work was outside its country of probable modern discovery before 1970 or was legally exported from its probable country of modern discovery after 1970. The museum should promptly publish acquisitions of archaeological materials and ancient art, in print or electronic form, including in these publications an image of the work … and its provenance, thus making this information readily available to all interested parties.” In the case of the Cleveland Museum of Art, the institution reports that it “has provenance information for the marble head back to the 1960’s, but has been unable to obtain documentary confirmation of portions of the provenance . . . .”

Documented information about an antiquity’s find spot, its archaeological context, and the artifact’s subsequent collecting history are important in order to learn about human history, to authenticate an artifact, to ensure compliance with national and international laws, and to preserve confidence in cultural institutions–especially those supported in part by taxpayer funds like the Cleveland Museum. That is why inquiry into the history of the Drusus Minor head is essential.

There is no reported information about the Drusus Minor head’s find spot or the archaeological context in which it was found. The Cleveland Museum explains that the head appeared on the market at auction in 2004. The museum was not the purchaser of the piece at the time, and the auction buyer remains unknown. Apparently there is no import or export paperwork supplied to the museum that may shed more light on either the object’s country of manufacture, the original seller of the piece, or any other data that might help complete a due diligence investigation.

The museum suggests an ownership history of the piece prior to the 1960’s but it concedes that its pre-2004 information is sourced in a “certificate of origin” produced a day after the auction by antiquities dealer and adviser Jean-Philippe Mariaud de Serres. He “assisted the prior owner and consigner, Fernand Sintes,” according to the Cleveland Museum’s object registry narrative. The certificate–not generated by the actual consignor but produced by an author who passed away five years ago–appears to be one of two primary sources relied on by the museum to establish the head’s collecting history. Meanwhile, the museum has not published any post-2004 collecting history information except to say that it bought the Drusus Minor head from Phoenix Ancient Art, an antiquities dealer with galleries in Geneva and New York.

Why an affidavit describing the ownership history was not produced by consignor Fernand Sintes to the Cleveland Museum is unknown. The circumstances under which a “certificate of origin” was produced by Mariaud de Serres after the 2004 purchase at auction are also not known. And how the Cleveland Museum obtained this “certificate of origin” remains unclear, particularly where the museum asserts that it has no information about the 2004 purchaser of the Roman head. There is also no information about who, when, or how the marble artifact entered the United States or how it was transferred from the unidentified auction buyer in 2004 to Phoenix Ancient Art, or to which location of Phoenix Ancient Art (Geneva or New York?). These are a handful of the many chain of custody questions that remain unresolved.

The chain of custody of an archaeological object is expected to come under scrutiny when accessioned by a major museum. Due diligence is anticipated to be used to investigate the object’s find spot and its subsequent ownership, possession, export, and import. And due diligence would particularly be expected in this case because the Drusus Minor head garnered much public attention in 2004, fetching a remarkably high purchase price.

The Cleveland Museum reports that the Drusus Minor head was listed at Piasa, Paris, Hôtel Drouot-Richelieu, Archéologie, 28–29 Septembre (Paris 2004) 74, lot. no. 340. That auction listing describes a marble head of Tiberius, which is in fact the Drusus Minor head. The Cleveland Museum explains in the object registry, “The work was initially identified and published as Tiberius, but was later (after 2007) recognized as a likeness of his son, Drusus Minor.”

Le Journal des Arts wrote in a 2007 article that the Drusus Minor/Tiberius head originally had an estimate of €100,000 ($123,150 USD in 2004) before it was purchased for over three times that amount, specifically $399,022 USD. The Drouot auction house continues to celebrate the sale on its web site:

“La plus haute enchère a été portée sur une tête monumentale représentant le portrait de l’Empereur Tibère, lot n°340, en marbre blanc à grains fins, Art Romain du Ier siècle, qui a été emportée à 324 013 €. Cette tête provenait d’une collection particulière.”

(Author’s translation: “The highest bid was given a monumental head representing the portrait of the Emperor Tiberius, Lot No. 340, in white marble-grain, first-century Roman Art, which was purchased for €324 013. This head came from a private collection.”)

As previously mentioned, the Cleveland Museum does not know who bought the archaeological object at this noteworthy sale. The museum, however, possesses the “certificate of origin” that, in all likelihood, would have been handed to the buyer. Did the museum specifically ask from where and under what circumstances the “certificate of origin” materialized as part of its due diligence investigation?

The Cleveland Museum, nevertheless, describes that Mariaud de Serres’ “certificate [of origin] stated the sculpture came from the collection of Mr. and Mrs. Sintes of Marseilles; that the sculpture had been in Mr. Sintes’s family for many generations; that the family’s name was Bacri; and that they had lived in Algeria since 1860.” To verify this information, the museum says that it turned to a second source of primary information. It “contacted Mrs. Sintes who confirmed on behalf of herself and Mr. Sintes that Mr. Sintes’ grandfather, Mr. Bacri, had owned the sculpture; that Mr. Sintes inherited the sculpture from his grandfather; that Mr. Sintes brought it from Algeria to Marseilles in 1960; that he had inherited it from his grandfather prior to bringing it to Marseilles; that the sculpture was sold at the Hôtel Drouot in 2004; and that they had worked with Mr. de Serres.”

There is no explanation why the museum did not contact Fernand Sintes. There is also no information about Mr. Bacri’s first name, how he came to own the artifact, or if there was paperwork specifically describing that Fernand Sintes would inherit the marble head after his grandfather’s death. Did the museum seek out other family members or those in the Bacri family to get a more complete collecting history? That is not known.

Additionally, there is no information about Mariaud de Serres’ exact role in the 2004 auction. Mariaud de Serres collected Roman-era antiquities, set up shop in Paris in the 1960’s, and is said to have created the “certificate of origin” on behalf of the Sintes couple. He reportedly opened a gallery in the 1960’s at the Palais Royal in Paris and was described in a 1999 New York Times article as “the Paris dealer who operates as a registered expert guaranteeing the authenticity of the items” at Dourot auctions. He died in 2007. A Christie’s February 2011 sale of his many lots of antiquities in Paris earned a total of € 2,737,912 ($3,763,807 USD). Many pieces offered were Roman. Prior to the sale, France’s Le Figaro paid tribute to the influential antiquities dealer by describing his many global travels around the Mediterranean basin, his advice to institutions and collectors, and his passion for collecting ancient artifacts. His specific involvement with the Drusus Minor head may or may not be of importance to understanding the object’s collecting history. But due diligence would require investigating what role, if any, he may have had acquiring the Roman head, facilitating its sale, and/or exporting the object.

The Drusus Minor head reached the shores of the United States at an unknown time and at an unknown place. What is known is that the 2007 Phoenix Ancient Art catalog titled Imago features the marble head as an image of Emperor Tiberius on the front cover and on pages 14 through 17. The catalog gives the archaeological piece pride of place, providing only the briefest collecting history.

The catalog also lists a bibliography with an interesting reference to a journal article by John Pollini titled “A New Marble Head of Tiberius.” Writing in Antike Kunst 48, 2005, pp. 55–72 pls. 7–13, the professor of art at the University of Southern California describes the previously unknown archaeological object:

|

| The Magdalene Tiberius Source: Antike Kunst |

“A magnificent, previously unpublished over life-size marble portrait of Tiberius (pl. 7, 1–4), which in the 1960s had been in a private French collection assembled in Marseilles, is to be found today in a private American collection. Now called the ‘Magdalene Tiberius’, after a member of the present owner’s family, this head is superbly carved in a luminous, fine-grained white marble with a slight beige patina that extends over the area of the break at the base of the neck. Although this portrait is said to have been found in North Africa, its provenance cannot be established with any certainty.”

A Roman marble head of Tiberius in a private collection in the 1960’s that is said to have been found in North Africa (perhaps Algeria?) sounds similar to the history of the Cleveland Museum head. The Magdalene Tiberius and the Cleveland Drusus also are similar in size, measuring 32.5 cm and 35 cm respectively. Moreover, both heads were acquired by sale in 2004, and they look to be, at least photographically, of similar quality and appearance.

Pollini tackles the question of provenance of the Magdalene Tiberius by assessing style and laboratory analysis. He writes:

“Although, as noted at the outset, the Magdalene Tiberius is said to come from North Africa, this provenance cannot be established with certainty. Indicating, in fact, the possible hand of a sculptor from Asia Minor are the particularly close comparisons in quality, subtlety of carving, and treatment of hairlocks that can be made between the Magdalene Tiberius and various portraits from this region . . . The marble of the Magdalene portrait also comes from the same area (Phrygia) as the head of Tiberius from Philomelion in the Louvre (MA 1255). Itinerant sculptors, including those from Asia Minor, worked in the wealthy cities of North Africa, where the lack of high quality white statuary marble necessitated the importation of marble for portraits.”

Pollini continues to speculate about the possible provenience of the Magdalene Tiberius based on laboratory analysis of the marble. Testing showed that the marble from the Magdalene Tiberius came from “ancient Phrygia in central west Turkey. The statistical analysis suggests two possible locations in Phrygia, Afyon and Usak. Afyon, ancient Dokimeion, is the most logical choice. . . . On the basis of the isotopic ratio analysis and what is known about the two quarries, Afyon appears to be the best choice for the provenance of the marble head.”

Were the Magdalene and Cleveland Museum marble heads owned by the same collector(s)? Were they unearthed from the same location? Did they come from Turkey? From Africa? Were they exported to the United States at the same time? Is the marble the same? Why did a sales catalog editor determine that Pollini’s “A New Marble Head of Tiberius” article should be included in the bibliography featuring the Cleveland head? Answers to these questions can aid a proper due diligence analysis.

Museums are invaluable institutions that transmit culture and knowledge to Americans. Continued public confidence in our cultural institutions is essential to maintaining a vibrant museum community. And the application of due diligence to the acquisition of archaeological heritage–as opposed to gentle inquiry–can help museums fulfill their legal, ethical, and social obligations.

In fact, AAMD ethics rules and professional practice guidelines place many responsibilities on a museum director that call for due diligence to investigate an object’s collecting history. These include duties that “[t]he director must ensure that best efforts are made to determine the ownership history of a work of art considered for acquisition;” that the “[t]he director must not knowingly allow to be recommended for acquisition—or permit the museum to acquire—any work of art that has been stolen (without appropriate resolution of such theft) or illegally imported into the jurisdiction in which the museum is located;” and that “the director is responsible for the daily monitoring of the institution’s compliance with laws and regulations.” AAMD says that “is committed to the exercise of due diligence in the acquisition process, in particular in the research of proposed acquisitions, transparency in the policy applicable to acquisitions generally, and full and prompt disclosure following acquisition.”

Among the several rules issued by the Report of the AAMD Task Force are:

- “Member museums should thoroughly research the ownership history of archaeological materials or works of ancient art (individually a “work”) prior to their acquisition, including making a rigorous effort to obtain accurate written documentation with respect to their history, including import and export documents.” (emphasis added)

- “Member museums should require sellers, donors, and their representatives to provide all information of which they have knowledge, and documentation that they possess, related to the work being offered to the museum, as well as appropriate warranties.” (emphasis added)

These rules naturally apply to the acquisition of the Drusus Minor head by the Cleveland Museum of Art .

Dr. David Gill’s Looting Matters is a blog worth following on this topic.

[Hyperlinks refreshed and updated on 4/20/17].

This post is researched, written, and published on the blog Cultural Heritage Lawyer Rick St. Hilaire at http://culturalheritagelawyer.blogspot.com. Text copyrighted 2012 by Ricardo A. St. Hilaire, Attorney & Counselor at Law, PLLC. CONTACT: www.culturalheritagelawyer.com